When we talk about children’s literature, we’re actually using an umbrella term for books that are marketed towards the ages from 0 all the way to the upper boundary of about 22.* I’m nearly 20 now, old enough to get judgmental side-eyes on the train from stodgy men who would prefer I subscribe to the romantic image of a young woman in a flowery skirt reading Henry James, and young enough that I haven’t forgotten yet the beauty and importance of the literature we create for children. Elitist “high literary” types have decried the books I’ve grown up with and loved as self-indulgent stories for a narcissistic generation. The snap judgment that children’s literature is less important than that for adults is a direct consequence of the impulse of older generations to criticize younger ones. Children and teenagers are not second class citizens. They are absolutely capable of dealing with complex issues and problems in fiction, and it’s time for adults to look at what they’re reading.

As I was growing up, I noticed that the media liked to mock the adolescent feeling of being misunderstood. I find this both incredibly heartless and cruel. As a society, why are we derisive towards the legitimate feelings of young people, and why are we insulting the books that shelter and comfort them? There is no one moment where a person grows out of childhood and into adulthood. As Sandra Cisnero so astutely points out in her short story “Eleven,” we are all effectively Russian nesting dolls, and the farther deep we look into ourselves the more of our younger selves we discover: “What they don’t understand about birthdays and what they never tell you is that when you’re eleven, you’re also ten, and nine, and eight, and seven, and six, and five, and four, and three, and two, and one.” To an extent, we are all misunderstood teenagers, or lost and lonely children. In order to live a fulfilling life, we all need to nurture our inner, younger selves the same way we nurture our adult selves, through stories.

With age comes fear. The world has changed drastically since my grandparents were young. In many ways, they don’t recognize the world around them, and they’re understandably shaken by this. But this fear of impending change is integral to human nature, and it can be lessened by a trip to your local independent bookstore, not just for teenagers scared of growing up, but for adults scared of what the younger generation is becoming. In 2012, 23.5% of the population was under 18. That is to say, almost a fourth of our population is set to inherit this changing world. If you want to look to the future, why not look to the literature that is shaping and inspiring a new generation of leaders, rather than decrying it as unimportant?

The Jenkins group ran a survey that discovered that 42 percent of college grads never read another book after college. I would absolutely assume that those who only read for school were never big readers in the first place, reading only what was assigned and never venturing onward. Beyond personal fulfillment, a society of nonreaders has dramatic consequences. There is a strong link between literacy rates and crime. Here’s the thing about children that read children’s books: they grow up to be adults reading books. The entire generation obsessed with Harry Potter is still reading and exploring new worlds, thanks to one amazingly powerful story. One of the great joys in my life is recommending books to children that I think they’ll love, and the world would be a better place if we all engaged in this practice of building a community of young readers who will one day be adult readers.

To use a real world example, as a society, we’ve decided it’s our responsibility to care for children. We do not leave them alone to weather the world on their own. How are we supposed to take care of people whose experiences are beyond our understanding? I have seen my peers absolutely killing themselves in order to achieve an academic level of perfection that is both mandated and unachievable. The struggle to achieve academically and the very real toll it takes on the mental health of students is beautifully captured in Ned Vizzini’s It’s Kind of a Funny Story, about a boy whose academic stressors trigger a mental health breakdown. Without reading books like Vizzini’s how are educators supposed to empathize and better care for their students? Studies have shown that reading good fiction encourages empathy, and an education system that requires students to sacrifice health to achieve is anything but empathetic.

These same people running our school system are the ones claiming the YA fiction that they love as “classics.” To these people I say: Catcher in the Rye is about teen angst. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is about racism and coming of age. To Kill A Mockingbird is about a ten year old and is taught in schools: try to tell me there’s no appeal to children there. Just as it would be wrong to deny the obvious value in these books, it’s wrong to deny the value in more contemporary works.

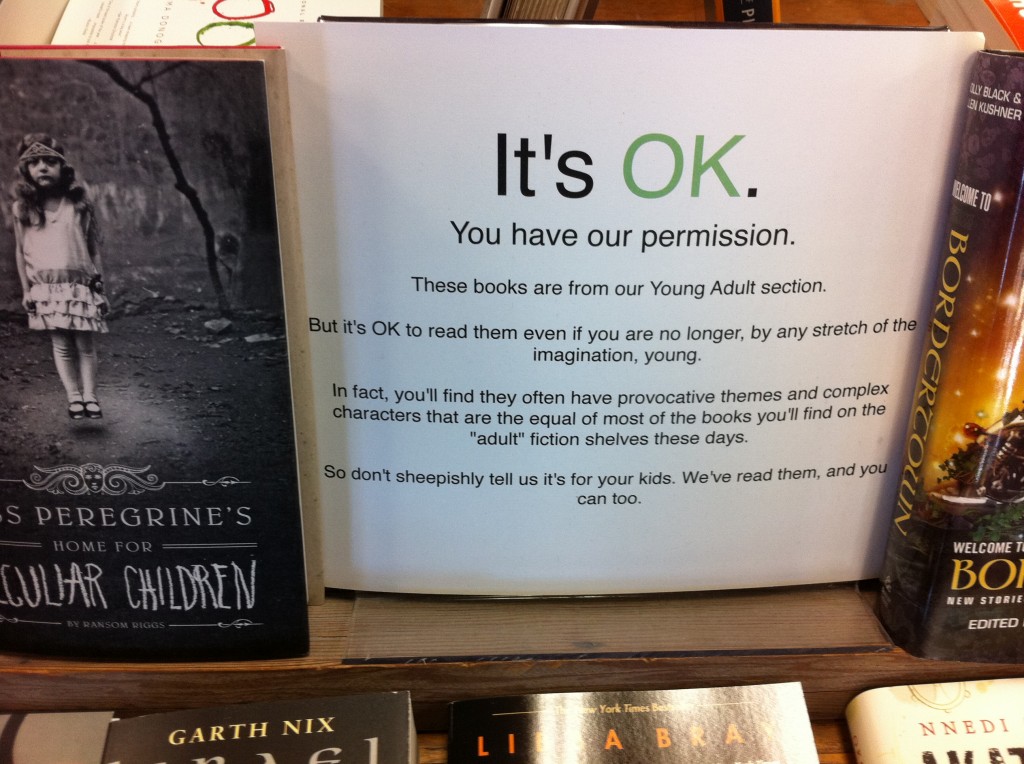

A final, crucial understanding to legitimizing these books to the wider literary community: YA is not a genre. Many people enjoy casually discarding “genre fiction” as unsophisticated or unimportant, and while this practice is flawed in and of itself, YA is not a genre. It’s as broad of a category as adult fiction and contains a myriad of genres within it. We have our romance novels and our fantasy quests, but we also have works of shocking insight, grace, and power, and these categories are not mutually exclusive.

It’s easy to think that as an adult, you don’t have anything in common with young people today. This is profoundly untrue. Good literature encourages its readers to step out of the concerns of their own life and into someone else’s. I may now be nearly a decade older than Anne Shirley when we first meet her in Anne of Green Gables, but there is no other literary figure with whom I identify more. One of the great triumphs of children’s literature is that given the chance, it will speak to anyone of any age, making better, more well rounded, more empathetic people.

*Books that go up this high in age are somewhat rare, but I recommend Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl.

No comments:

Post a Comment